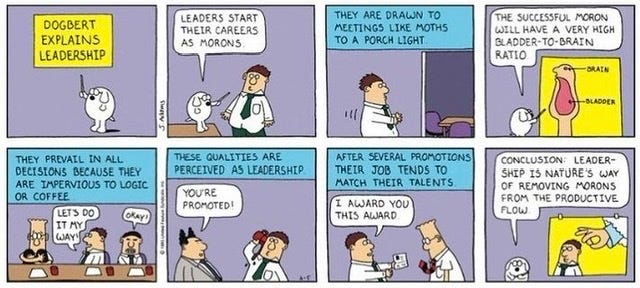

Dilbert Principle

Will we ever learn?

FOMO

The unraveling of society continues, and it’s impacting corporate hell. Everyone I talk to complains about how the “good talent” is walking out the door and getting 30-40% pay increases from competitors. Adding salt to the wound is the challenge to attracting top talent for many long-established companies. The result is more work on the people still with the company, with minor prospects for upward mobility. Bitches, FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) is real!

If you work for a traditional company, the view to the top is a group of out-of-touch executives counting the days until retirement, a sea of purposeless middle managers, and a handful of hustling, less-experienced associates doing most of the heavy lifting. You’re not alone - in 1995, Dilbert coined the term the Dilbert Principle, explaining that:

Leadership is nature’s way of removing morons from the productive flow

At the time, this helped us reconcile the anger and frustration we were all feeling as we watched incompetent people routinely get promoted. But after some digging, I learned this theme has persisted across many generations, even as early as the 1700s! Today, I’ll focus on the modern examples.

Fool me once; shame on you

In June of 1949, George Orwell published his seminal work, Nineteen Eighty-Four. In it, he opines about why ineffective people get promoted:

Between the two branches of the Party, there is a certain amount of interchange, but only so much as will ensure that weaklings are excluded from the Inner Party and that ambitious members of the Outer Party are made harmless by allowing them to rise

The timing makes sense - after the United States returned victorious from WWII, many Baby Boomers started careers in corporate America. While the roaring 50s brought optimism manifesting in wings on everything from cars to toasters, fears of Big Brother and the thought police showed the darker side of conformity.

Then came the Peter principle - a theory on organizational hierarchy coined by Canadian educational scholar and sociologist, Dr. Laurence J. Peter. He observed that:

People in a hierarchy tend to rise to a level of respective incompetence

After many years of research, Peter and Raymond Hull summarized the concept in their 1969 book The Peter Principle (William Morrow and Company). Interestingly, the book was intended as a satire but became the source of many other commentaries and research on organizational hierarchy.

In 1989, Scott Adams started publishing his now ubiquitous comic strip, Dilbert. The story features Dilbert, a micromanaged, white-collar engineer working in Silicon Valley. I entered corporate hell in 1988, so Dilbert helped me through all my ups and downs.

It's been a few decades since Dilbert, and we have the new AppleTV+ series, Severance. Created by Ben Stiller and Aoife McArdle, the plot follows Mark, an employee of Lumon Industries, who agrees to a "severance" program in which his home-life and work-life memories get separated. Mark's boss, Ms. Cobel, spoke of her views on keeping employees satisfied:

The surest way to tame a prisoner is to let him believe he's free

I’m no data scientist, but four points make a trend. Fool me once; shame on you. Fool me twice; shame on me. Fool me four times; shame on us all. How am I coping? I’m rethinking how many more rungs I want to climb on the ladder. Maybe I should write a book about it.

In answer to your question, No; we will never learn. At least not right away. We've only been a non-agrarian culture for fewer than 100 years. That's not enough time to evolve to an enlightened level as corporate workers. So I like to garden.

"Fool me four times; shame on us all" Can't say I've heard that before. Funny as hell.